One of the Newest Threats on the Street: Gray Death

Illicit drug dealers seem to think it’s some kind of grim game to give their drugs catchy names. Heroin dealers in the Northeast have long used the gimmick of stamping small glassine envelopes with names like “Prada,” “Bugatti,” or “Kiss of Death.” These stamps were supposed to identify a particular mixture of drugs that might become popular if they were found “pleasingly” potent, leading customers to come back for more.

A few years ago in Plano, Texas, drug dealers enticed young people to try a new drug they were marketing nicknamed “cheese.” They didn’t tell these young teens that the mixture contained heroin. Dozens of young people died before the word got out that this mixture was both addictive and deadly.

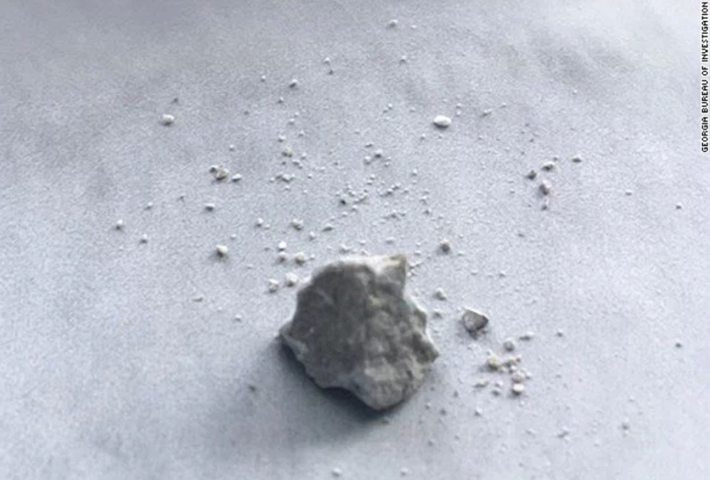

In a similarly grim manner that may also be trying to be ironic, drug dealers have taken to mixing a number of deadly drugs, coming up with a crumbly gray product they have nicknamed “gray death.” The problem is that it lives up to its name by killing their customers.

The drug has been found mostly in the Southeastern United States, plus Indiana, Ohio, Texas, Wisconsin and New York. In 2015 and 2016, 45 people died. In the first few months of 2017, Georgia authorities seized 50 batches of the drug and in May, they alerted the public that 17 people in the state had succumbed to the drugs commonly found in this product.

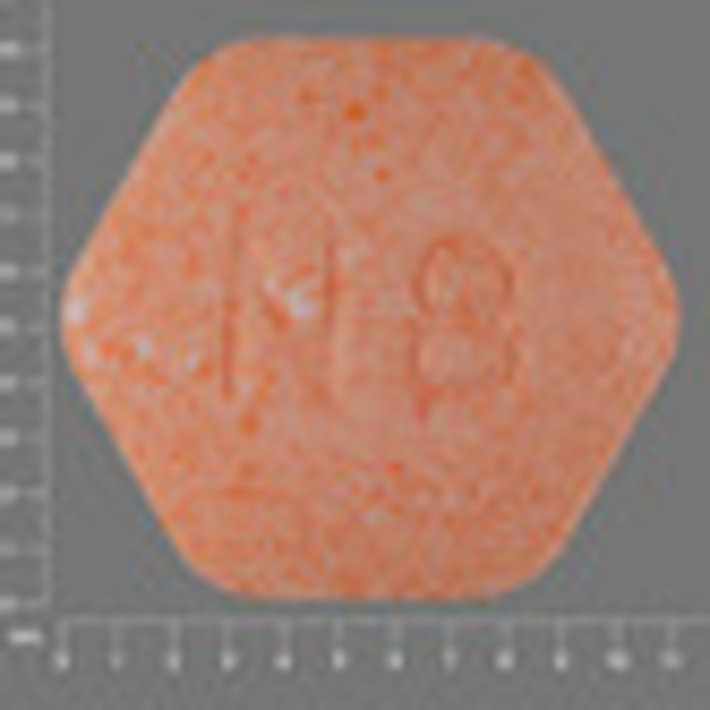

It’s hard to track the presence of this drug exactly because the ingredients are not always the same. It generally contains some form of illicitly-manufactured fentanyl, possibly furanylfentanyl. A chemically-similar drug identified as U-47700, nicknamed “pink” when it is found on its own, may be included, along with heroin. The vastly potent form of fentanyl used for large animals, carfentanil, may also found in the dull gray rocks sold as gray death.

Numbers of Reported Incidents Can Be Misleading

Reports of the number of overdoses resulting from gray death may be inaccurate. That’s because a toxicology screen after an overdose death may test for one or two opioids but may not detect all the ingredients commonly included in this drug. Some deaths may be associated with fentanyl or heroin when they are, in fact, the result of this grimly-named combination.

A rational person might wonder why anyone would bother naming a drug combination something as ugly as gray death. Or why a person might actually seek out a combination known to include fentanyl, ten times stronger than heroin, or carfentanil, thousands of times stronger than heroin. An addicted person who no longer gets a high from heroin will often seek out a drug with a more powerful effect, even if that drug has the potential to cause an overdose.

In fact, this person no longer has a rational grip on his own survival. He (or she) only seeks to prevent the desperate sickness that arrives within hours if a dose of opioids is missed.

This desperation and the unfathomably dangerous drugs on the market are the drivers for the increasing rate of overdose deaths in America. The presence of naloxone in the hands of first responders to bring those who overdose back from the brink of death may be the only thing keeping our losses from skyrocketing even higher.

®

®